Peyton Randolph House Archaeological Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 00Originally entitled: "A View From the Top : Archaeological Investigations of Peyton Randolph's Urban Plantation"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 175

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1996

A VIEW FROM THE TOP:

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF PEYTON RANDOLPH'S URBAN PLANTATION

Department of Archaeological Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

February, 1988

ABSTRACT

An intensive archaeological investigation of the back yard of the Peyton Randolph House, an early eighteenth-century structure located within the Historic Area of Williamsburg, took place from the summer of 1982 to the spring of 1985. Although previous archaeological work had been done during the 1930s and 1950s, new methods and techniques as well as a more modern research design required further, more detailed exploration of the area.

In addition to the task of uncovering the foundations of the fifteen outbuildings that stood behind the house during various periods, the project was used as an experimental laboratory for testing archaeological methods and techniques new to Colonial Williamsburg Foundation archaeology. Such methods include the Harris Matrix System, computer entry of context and artifact data, and block excavation.

Aside from the outbuilding foundations, such features as walkways, fence lines, garden patches, and work areas were defined. Beginning with the assumption that changes in the property ownership is reflected in the archaeological record and can be evidenced in the analysis of the site, the archaeology culminated in an interpretation of the way the yard was used during various periods spanning over 250 years.

The excavation performed another important function for the Foundation: the interpretation of an on-going archaeological site to Colonial Williamsburg visitors. This aspect of the project proved quite successful, so much so, in fact, that the experience was repeated in 1987 with an exhibition dig at the nearby Brush-Everard property.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| List of Figures | i |

| List of Photographs | iii |

| Introduction | v |

| Acknowledgments | vi |

| Chapter 1 - Location, Historical and Environmental Background | 1 |

| Chapter 2 - Previous Archaeology | 9 |

| The First Excavations | 9 |

| The Second Excavations | 11 |

| The Third Excavations | 11 |

| Chapter 3 - Method and Technique | 13 |

| Excavation | 13 |

| Soil | 18 |

| Flotation | 18 |

| Chemistry | 18 |

| Artifacts | 19 |

| Special Studies | 19 |

| Pollen and Parasite Analysis | 19 |

| Thermoluminescence | 20 |

| Dendrochronology | 20 |

| Archaeo-botanical Analysis | 21 |

| Faunal Analysis, Preliminary Report | 21 |

| Chapter 4 - Description of Major Finds, 28G Area | 23 |

| Structure A - Early Eighteenth-Century Dwelling | 25 |

| Structure B - Outbuilding | 41 |

| Structure C - Outbuilding | 44 |

| Structure D - Outbuilding for Structure A | 46 |

| Structure E - Granary (?) | 49 |

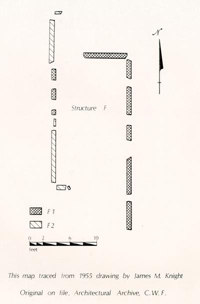

| Structure F - Unidentified Building | 53 |

| Topsoil | 54 |

| Modern Disturbances | 56 |

| Plowzone | 58 |

| Brown Sandy Loam 1 and 2 | 60 |

| Walkway #1 | 89 |

| Walkway #2 | 92 |

| Fence Lines | 95 |

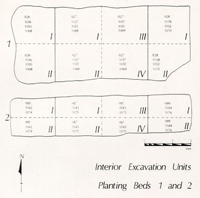

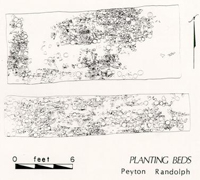

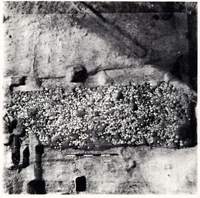

| Planting Beds | 102 |

| Middle Plantation Features | 111 |

| Chapter 5 - Description of Major Finds, 28H Area | 115 |

| Modern Intrusions and Topsoil | 115 |

| Marl Walkway #1 | 118 |

| Marl Walkway #2 | 119 |

| Refuse Layer | 121 |

| "Clean" Brown Loam | 126 |

| Fence Lines | 129 |

| Structure G - Dairy (?) | 133 |

| Structure H - Smokehouse (?) | 135 |

| Structure J - Dwelling/Second Kitchen | 138 |

| Structure K - Third Kitchen | 141 |

| Structure L - Fourth Kitchen | 143 |

| Structure M - First Kitchen | 151 |

| Structure N - Shed | 153 |

| Area 28B | 155 |

| Structure R - Unidentified Building | 155 |

| Structure Q - Unidentified Building | 155 |

| Structure P - Dairy | 156 |

| Well | 158 |

| Chapter 6 - Interpretation and Conclusions | 161 |

| Chapter 7 - Artifact Catalog | 183 |

| References Cited | 211 |

| Appendix 1 - | Peyton Randolph's Inventory |

| Appendix 2 - | Humphrey Harwood's Ledger |

| Appendix 3 - | Archaeological Report, September 1939 |

| Appendix 4 - | Archaeological Report, 1978 |

| Appendix 5 - | Pollen and Parasite Analysis |

| Appendix 6 - | Macrofossil Analysis |

| Appendix 7 - | Oral History |

| Appendix 8 - | Dendrochronology Report, 1983 |

| Appendix 9 - | Thermoluminescence Report |

| Appendix 10 - | Dendrochronology Report, 1984 |

| Appendix 11 - | Analysis of Twentieth-Century Cistern Debris |

| Appendix 12 - | Analysis of Oyster Shell |

| Appendix 13 - | Analysis of Faunal Remains from Planting Beds |

| 1.Randolph House and Property Location | 2 |

| 2.The "Frenchman's Map" | 3 |

| 3.Context Record Form | 16 |

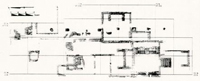

| 4.Overall Map of the Excavation Area | 23 |

| 5.Placement of Joist Nails, Interior of Structure A | 26 |

| 6.Detail of Corner Fireplace, Structure A | 27 |

| 7.Profile of Standing Balk in Structure A | 29 |

| 8.Cross-mends to 1955 Trench Fill, Structure A | 30 |

| 9.Structure A, Artifact Scatters | 32 |

| 10.Distributions of Selected Artifacts in Plaster Layer and Below Plaster Layer | 33 |

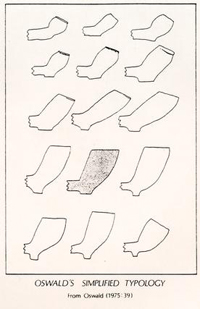

| 11.Oswald's Simplified Typology | 34 |

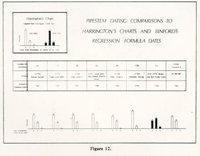

| 12.Pipestem Dating: Comparisons to Harrington's Charts and Binford's Regression Formula Dates | 35 |

| 13.Ware Types - Specific Categories | 36 |

| 14.Ware Types - General Categories | 37 |

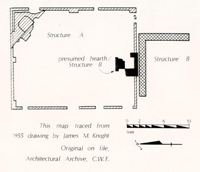

| 15.Brick Feature over South Wall of Structure A (from J.M.K. map) | 42 |

| 16.Structure F (from J.M.K. map) | 52 |

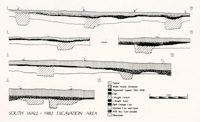

| 17.South Wall - 1982 Excavation Area | 54 |

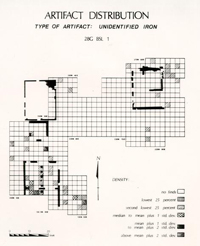

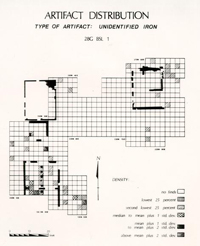

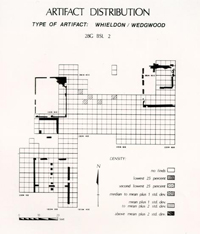

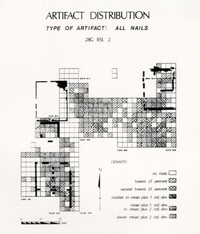

| 18.Artifact Distribution Based on Piece-Plotting | 62 |

| 19.Artifact Distribution Based on 2.5 x 2.5 Foot Sub-units | 62 |

| 20.Artifact Distribution Based on 5 x 5 Foot Units | 62 |

| 21.Artifact Distribution Based on 10 x 10 Foot Units | 62 |

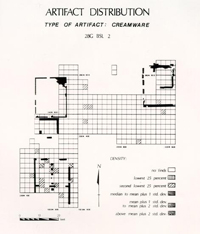

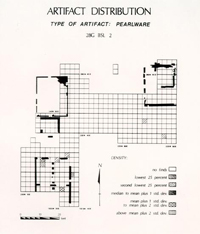

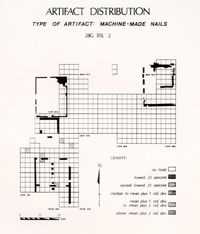

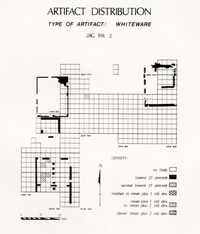

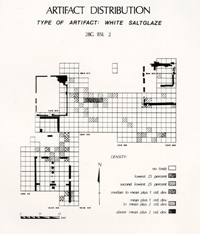

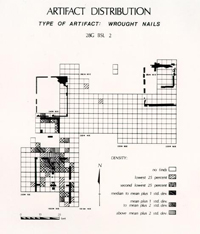

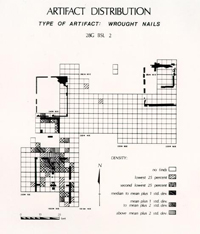

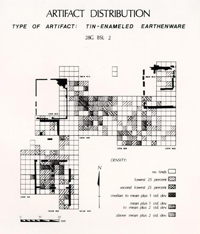

| 22-30.Artifact Distribution Maps, BSL1 | 64-77 |

| 31-44.Artifact Distribution Maps, BSL2 | 78-86 |

| 45.Ceramic Size Form | 88 |

| 46.Walkway #1, 28G Area | 90 |

| 47.Walkway #2, 28G Area | 93 |

| 48.Eastern North-South Fence Line | 96 |

| 49.Western North-South Fence Line | 97 |

| 50.East-West Fence Line | 98 |

| 51.Central North-South Fence Line | 100 |

| 52.Excavation Divisions, Planting Beds 1 and 2 | 104 |

| 53.Detail of Paving Material, Planting Beds 1 and 2 | 105 |

| 54.Middle Plantation Era Boundary Ditch with Associated Post Holes | 111 |

| 55.Marl Walkway #1, 28H Area | 118 |

| 56.Marl Walkway #2, 28H Area | 119 |

| 57.Refuse Layer, 28H Area | 121 |

| 58.Artifact Distribution, Clean Brown Layer | 126 |

| 59.Fence Line | 129 |

| 60.Admiral Vernon Commemorative Buckle | 139 |

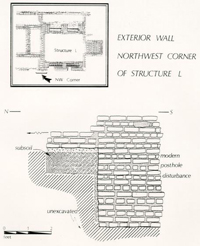

| 61.Exterior Northwest Wall, Structure L | 147 |

| 62.Remains of Piers Supporting Covered Way | 148 |

| ii | |

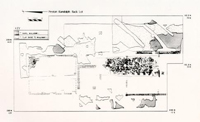

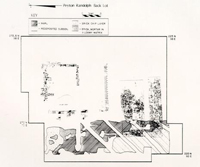

| 63.Periodization Map 1 (Pre-1699) | 163 |

| 64.Periodization Map 2 (1715-1724) | 165 |

| 65.Periodization Map 3 (1724-1737) | 167 |

| 66.Periodization Map 4 (1737-1755) | 168 |

| 67.Periodization Map 5 (1755-1775) | 170 |

| 68.Periodization Map 6 (1783-1800) | 172 |

| 69.Periodization Map 7 (1800-1860) | 174 |

| 70.Periodization Map 8 (1860-1900) | 176 |

| 71.Periodization Map 9 (1900-1920) | 178 |

| 72.Periodization Map 10 (1920-1938) | 179 |

| 73.Periodization Map 11 (1938-1985) | 180 |

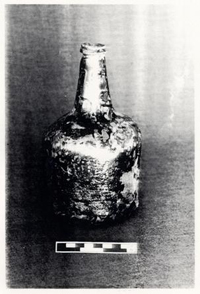

| 74.English Beverage Bottle | 185 |

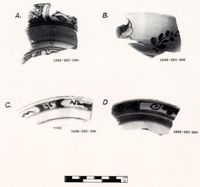

| 75.Stoneware Tankards | 187 |

| 76.English Delftware Fireplace Tile | 189 |

| 77.Chinese Porcelain Vessels | 191 |

| 78.English Delftware Vessels | 193 |

| 79.Staffordshire Red Sandyware and Colono-Indian Ware Vessels | 195 |

| 80.Chinese Porcelain Vessels | 197 |

| 81.English Glass Beverage Bottles | 199 |

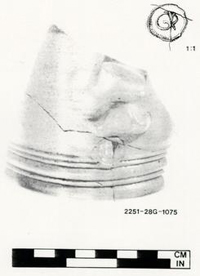

| 82.Fulham-Type Brown Stoneware Tankard | 201 |

| 83.English Delftware Vessels | 203 |

| 84.Coarseware Vessels | 205 |

| 85.Glass Bottle Seal | 207 |

| 1.Peyton Randolph House - South Elevation | 1 |

| 2.Reconstructed Outbuilding - Structure N | 9 |

| 3.East Elevation of House, Before Restoration | 10 |

| 4.Excavation of the Foundations of Structure S in 1938 | 10 |

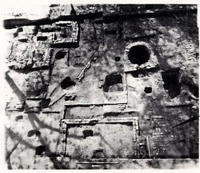

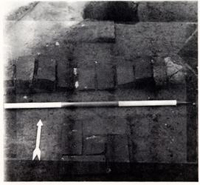

| 5.Structure A | 25 |

| 6.Rowlock Wall Under Foundations of Structure A | 27 |

| 7.Detail of Fireplace "Wing" | 28 |

| 8.Structure B | 41 |

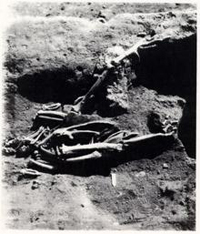

| 9.Articulated Remains of Rooster | 43 |

| 10.Articulated Remains of Duck | 43 |

| 11.Structures C and D | 44 |

| 12.Structure D | 46 |

| 13.Structure E | 49 |

| 14.Detail of Collapsed Pier, Structure E | 50 |

| 15.Miller, Skillman, and Donegan Houses | 55 |

| 16.Post Hole Through East Wall, Structure E | 58 |

| 17.Walkway #1, 28G Area | 89 |

| 18.Walkway #2, 28G Area | 92 |

| 19.Eastern North-South Fence Line | 95 |

| 20.Different Uses of Back Lot on Either Side of Eastern Fence Line | 96 |

| 21.Differential Drying of Planting Beds 1 and 2 | 102 |

| 22.Planting Beds 1 and 2, Unexcavated | 103 |

| 23.Overall, Planting Beds 1 and 2 | 106 |

| 24a.Planting Bed 3, Looking South | 107 |

| 24b.Planting Bed 3, Looking North | 107 |

| 25.Planting Bed 4 | 109 |

| 26.Telephone Line in 28H Area, 1955 | 116 |

| 27.Late Nineteenth-Century Windmill at Peyton Randolph Site | 116 |

| 28.Structure G | 133 |

| 29.Structure H | 135 |

| 30.Surviving Outbuildings Behind the Peyton Randolph House , c. 1900 | 137 |

| 31.Structure J | 138 |

| 32.Structure K | 141 |

| 33.Structure L | 143 |

| 34.Structure L, Cement Removed | 145 |

| 35.Interior, East Wall, Structure L | 146 |

| 36.Circa 1870 Photograph Showing Kitchen Building Behind Main House | 149 |

| 37.Structure M | 151 |

| 38.Structure N (1938) | 153 |

| 39.Structures P, Q, and R | 156 |

| 40.The Well | 158 |

| 41.Effects of Tunnel Construction on Structure S | 162 |

| 42.South Elevation of House, circa 1870 | 175 |

INTRODUCTION

The last phase of archaeology undertaken on the Peyton Randolph lot (Colonial Lot 207?) was begun July 7, 1982, and continued through early spring of 1985. The project was funded by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund as part of a gift to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for intensive archaeological investigation and the eventual reconstruction of the appropriate outbuildings behind the house. The project was the first major undertaking of the newly-established Office of Excavation and Conservation, now the Department of Archaeological Research, under the direction of Marley R. Brown III.

The overall project supervisor was Robert C. Birney, Senior Vice President, Education, Preservation, and Research.

Adrian Praetzellis was the field, supervisor for the first two months of the project, after which Linda K. Derry served in that capacity until the spring of 1983. From spring of 1983 until the culmination of the field work in 1985, Andrew C. Edwards was the site supervisor, assisted by Roy A. Jackson.

The research design for the archaeology of the site was two-fold in nature. Primarily, the purpose of the excavations was to produce an accurate chronology of the lot, including structures and activity areas from the time of the construction of the main house in the second decade of the eighteenth century to the present. In addition to this rather straightforward periodization of the investigated area, the Peyton Randolph excavation served as a proving ground for testing the viability of new recovery techniques, the computerization of site data, and the institution of various recording forms. The value of data recovered from contexts disturbed by previous excavations was also tested at Peyton Randolph. The methods and techniques used in the excavation process proved to be invaluable in subsequent archaeological endeavors throughout the Historic Area.

The two-fold research design at Peyton Randolph has spawned two types of reports on the archaeology. This, the descriptive and interpretive report, addresses the primary periodization approach to the lot, outlining the temporal frames for possible reconstruction purposes. A second, more academically oriented monograph is in the process of production and will address the more theoretical aspects of recovery technique, in-depth analysis of artifact types and their distribution, and the relative importance of data from disturbed contexts.

The following report is essentially descriptive in nature, outlining the various structures and significant features discovered or rediscovered during the course of excavation. The final chapter attempts to place these structures and features into various time frames and explain as best as possible the metamorphosis of the Randolph House back lot from the Middle Plantation period to the present.

An excellent architectural assessment of the main house and the outbuilding foundations was submitted by Willie Graham of Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Architectural Research in December of 1985 (Graham 1985). That report, the house history (Stephenson 1952, revised by Carson in 1967), the documentary report (Gibbs 1978), and this report should provide a firm basis for the reconstruction and interpretation of the Peyton Randolph outbuildings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Peyton Randolph Project, undertaken by the Office of Excavation and Conservation, involved many people and several departments over the past four years. It is nearly impossible to specifically acknowledge everyone who has had a part in the project's successful completion. The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions:

Robert C. Birney, Senior Vice-President, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CWF), who not only guided the funding of the projects, but offered his support, ideas, and knowledge throughout the excavations and report-writing period.

Ivor Noël Hume, Foundation Archaeologist (Rtd.), CWF, who examined several important features found on the site and offered his expert interpretation and advice. Mr. Noël Hume also began the preliminary excavations around Structure A in 1978.

Niel Black, Miller, CWF, and Windmill staff who cheerfully tolerated the horde of muddy excavators sharing the Windmill employee lounge, the visitors' many questions about the archaeology, and the often unsightly mess associated with excavation.

Dennis O'Toole, Vice-President, Historic Area Programs and Operations, CWF, and his staff of outstanding interpreters, who, through heat, rain, and chilling winds often talked themselves hoarse ably interpreting the sometimes confusing process of archaeology to throngs of visitors.

Gertrude Deversa, Life Tenant, Peyton Randolph House, who also cheerfully tolerated the disruption caused by the archaeological process, provided us valuable information about the house and yard, and more than once provided refreshments to a hot and tired group of excavators.

The Peyton Randolph House Staff, who never complained of the inconvenience caused by the archaeology, answered many visitor questions, and often tracked down one of the supervisors or crew in order to deliver telephone messages.

Ed Chappell, Willie Graham, and Nick Pappas who avidly followed the progress of the excavations, brought in architectural experts, helped sort out the profusion of foundations, and always offered encouragement.

James Knight, who directed the previous excavations in the 1930s and again in the 1950s at Peyton Randolph. His recollections and advice were invaluable.

Colonial Williamsburg's Landscape Department for providing the cherry picker for aerial photographs and for helping us keep the site looking as good as possible.

viiThe excavators and field technicians who accomplished the task included:

| Ramona Avallone | Tom Hayman | Roni Polk |

| Steve Alexandrowicz | Jeff Holland | Janet Rocha |

| Tad Baker | Alison Helms | Don Roland |

| Andrew Barski | Patrice Jeppson | Barbara Seligmann |

| Steve Beauter | Elizabeth Jorgensen | Sam Shogren |

| Ross Becker | Simon Krauss | Susan Stanford-Stoney |

| Amy Bennett | Anne Kushnick | Tony Stockbridge |

| Lisa Broberg | Rebecca LaFontaine | Chris Styrna |

| Greg Brown | Mark Lawall | John Sprinkle |

| Mark Canada | Melanie Liddle | Nate Smith |

| Mark Cravalho | Mike Meyer | Charles Thomas |

| Jim Csigas | Linda Myers | Karin Vanderpeer |

| Felicity Devlin | Susan Mira | Lucie Vinciguerra |

| Robin Duffy | Charlie McNutt | James Wilson |

| Andrea Foster | David Muraca | Wheeler Wood |

| Cecile Gaskell | Dan Nolin | Ian Wilmshurst |

| Lynn Gentemann | Ann Plane | Mary Zylowski |

| Hannah Gibbs | Tom Polk |

The following members of the Laboratory Staff expertly identified and processed the 250,000+ artifacts recovered:

| Susan Alexandrowicz | Leslie McFaden |

| Elizabeth Bush | Lisa Pittman |

| Jenny Carr | Monica Perry |

| Tara Goodrich | Kathleen Pepper |

| Paula Lampert | Wright Robinson |

Adrian Praetzellis was the first crew chief at Peyton Randolph, getting the excavations off to a good start.

Len Winter was instrumental in establishing the initial grid system.

Charles Hodges, Staff Archaeologist at Flowerdew Hundred was kind enough to secure a transit for the above exercise.

The following staff members played very important roles in the completion of the project:

- Patricia Samford for technical assistance

- Robert Hunter for technical assistance, computer

- William Pittman for supervision of the lab and aid in procurements

- viii

- Virginia Caldwell for drafting and surveying assistance

- June (Nan) Reisweber for administrative assistance and patience

- Curt Moyer for expert conservation of artifacts

- William Adams for advice and guidance

- Tamera Mams for photographic assistance

- George Miller for technical assistance, artifacts

- Gregory Brown for proof-reading, editing, and offering numerous excellent suggestions about content and style. His expertise in the use of WordPerfect and the Hewlett Packard LaserJet+ were invaluable in the report production.

- Hannah Gibbs McKee for her excellent design creations and her exhaustive work in actually laying-out the report and coordinating its production.

CHAPTER ONE:

LOCATION, HISTORICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL

PHOTO 1 — Peyton Randolph House — South Elevation

PHOTO 1 — Peyton Randolph House — South Elevation

The Peyton Randolph House (see above) is located within the Historic Area of the City of Williamsburg, on the northeastern corner of Nicholson and North England Streets (Fig. 1). The so-called Frenchman's Map, allegedly drawn by an unknown French military cartographer in 1782, clearly depicts the house with the older west and east wings connected by the central section in much the way the house stands today (see Fig. 2). It does not, however, indicate any outbuildings associated with the structure. Very few dependencies appear on the early map, probably because of the relative unimportance with which such structures were viewed. The front of the Randolph House faces Market Square to the south, as it has since the construction of the mid-section, probably in the 1750s. Before this time, when the present west wing stood alone, the house would have likely faced west, towards Palace Green, with the few outbuildings placed along the north side of the structure, perhaps facing west as well.

This change in orientation was probably a reflection of several occurrences in the period from 1715 to 1760. Market Square became a popular area for trading, probably acquiring a market house by 1757, and had gained a public atmosphere. 2 The present court house was built on the Green by 1770, further enhancing the popularity of the area. The change from west to south may also have been influenced by the construction of Tazewell Hall by Peyton's brother John Randolph about 1762. Tazewell Hall is located at the end of South England Street, almost directly south of the Peyton Randolph House. Hampered only by the Powder Magazine, the two brothers could have their houses facing each other, sharing the "vista."

Whatever the reason, the effects of the re-orientation probably resulted in the rearrangement of the dependencies. This change is reflected in the archaeological findings and is the crux of the three-year investigation. The change, and the supporting evidence, will be elaborated upon in the interpretive section of this report.

Figure 1 — Randolph House and Property Location

Figure 1 — Randolph House and Property Location

Figure 2 — The "Frenchman's Map"

Figure 2 — The "Frenchman's Map"

LOT HISTORY

The use of the area presently occupied by the Peyton Randolph site during the Middle Plantation era (1634-1699) is generally unclear. The only archaeological feature representing this time period was a boundary ditch crossing the site in a northwest-southeast direction. This ditch may be related to the palisade which was built in 1634, traversing the entire Middle Peninsula between what are now called College and Queen's Creeks. No other conclusively seventeenth-century or aboriginal features were encountered during the course of excavation.

The first historical documentation involving the area under investigation was on November 11, 1714, when the Trustees of the City of Williamsburg conveyed eight lots to William Robertson. The lots sold to Robertson were numbered 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 207, and 208 on the City Plat. Unfortunately, the first plat of the city no longer exists, and the exact location of the numbered lots is not known. However, careful examination of the surviving historical records has placed the lots mentioned above in the block bounded by the eighteenth-century locations of Scotland Street on the north, N. England Street on the west, Nicholson Street on 4 the south, and Queen Street on the east. Their configuration was probably as follows:

Written in the conveyance of the eight lots to Mr. Robertson was the stipulation that he build upon each of the lots within two years, or they would revert to the Trustees:

… that if the said Wm. Robertson his heirs or Assigns shall not within the space of Twenty four Months next ensueing the date of these Presents begin to build & finish upon Each Lott of the said granted Premisses One good Dwelling house or houses of such dimensions & to be placed in such manner as by One Act of Assembly made at the Capitol the 23d day of October 1705 … then it shall & may be lawful to & for the said Feoffees or Trustees & their succesors Feoffees or Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & Erecting … to have hold & Enjoy in a like manner as they might otherwise have done if these Presents had never been made (Stephenson 1952, from York County Deeds and Bonds, III, 28-29).

Apparently Robertson found himself unable to meet these requirements, because on November 19, 1715 he sold lots 233 and 234 to Philip Ludwell. On April 20, 1717 the Trustees gave title of lot 232 to John Tyler, who was apparently already living on it. Again, on January 17, 1718 the Trustees conveyed title to lot 235 to Samuel Cobbs, also already in possession. Robertson was able to retain four of the lots, however, until 1723 when he sold them to John Holloway. At that time the lots contained several houses, orchards, and a windmill (Stephenson 1952).

In July of 1724, only six months after he had purchased the four lots, Holloway sold one lot, probably 237, to John Randolph. The record of sale describes the lot as "… adjoining to the Lot whereon the said John Randolph now lives …" The record also mentions "messuage" on the lot, which probably describes a building built by Robertson soon after the initial purchase in 1714. How Randolph acquired the adjacent lot on which he lived at the time of this sale, presumed to be 207, is unclear. There is also a real possibility that the lot Randolph bought from Holloway was actually 207 and he was already residing in Structure S on lot 237. Since there is no record of the prior sale in the York County records, the assumption is that the transaction was recorded in the Hustings Court or in General Court, the records for which have not survived. Randolph sold the only other lot he owned (174) to Archibald Blair the same day in 1724 that he bought 237. The exact location of lot 174 is not known, but consensus has placed it across N. England Street on the southwestern corner of England and Scotland Streets.

John Randolph, new owner of lots 207 and 237, was born at his family home at Turkey Island in 1693. He attended the College of William and Mary from 1709 5 to 1711, becoming Deputy Attorney General for the Counties of Charles City, Henrico, and Prince George in 1712. Between the years 1715 and 1717, he traveled to England to study law. Upon his return to Williamsburg, Randolph was appointed clerk of the House of Burgesses. After serving as agent for the Colony for many years, in 1732 he became the only colonial Virginian to be knighted. He was elected Speaker of the House of Burgesses in 1734 and remained "Mr. Speaker" until his death in 1737.

John Randolph married Susannah Beverley of Gloucester County around 1718. At the time of his death, four children were surviving: Beverley, born c. 1720; Peyton, born c. 1721; John, born c. 1727; and Mary, whose birth and death dates are not known. Susannah Randolph survived her husband and remained owner of the house until her death sometime after 1754. It is at this date that the last historical reference to Lady Randolph appears. The exact date of her death and place of burial, however, are unknown.

The Randolph's eldest son Beverley resided in Gloucester, becoming a Burgess for the College and later Sheriff of Gloucester County. Younger son John Randolph (often known as John Randolph the Tory) became a prominent lawyer, Burgess, Attorney General and Speaker of the House. He was also quite interested in horticulture, probably writing A Treatise on Gardening by A Citizen of Virginia around 1765. Perhaps wanting a home commensurate with his brother's, he built Tazewell Hall, the largest private residence in the city, on South England Street. When the break with Great Britain came, John fled to England. His body was returned to Williamsburg after his death in 1784 and was buried alongside his father and brother in the vault at the College of William and Mary.

Peyton Randolph, just as his father and brother, attended the College of William and Mary and studied law in England. He was admitted to the bar on February 10, 1742/3 and began his career as Attorney General for the Colony on May 7, 1744. Soon afterward, on March 8, 1745/6, he married Betty Harrison of Berkeley. They resided at his mother's house where Peyton had grown up. Peyton's public life continued in various assignments as Attorney General, with increasing involvement in inter-colonial affairs. He was elected Speaker of the House in 1766. As the problems leading to the eventual revolution were becoming more apparent, Peyton Randolph was increasing his contact with prominent personalities from the other colonies. In 1774 the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, and Randolph was unanimously elected president. He was also president of the Second Continental Congress, held on May 10, 1775. Declining health prevented Peyton Randolph from continuing to preside over the Congress, although he was in attendance to see John Hancock elected to his former position. Peyton Randolph died in Philadelphia of what seems to have been a stroke at about eight in the evening on October 22, 1775. He was buried in the chapel at the College of William and Mary.

Peyton Randolph was survived by his wife, Betty, who inherited his entire estate since the couple had no children. Betty Randolph also survived the Revolution and the occupation of the city of Williamsburg by Lord Cornwallis' troops. She died in 1783 and was probably buried in the vault at the College with her husband.

6The following advertisement of public auction appeared in the Virginia Gazette on February 15, 1783:

TO BE SOLD, By public auction, in Williamsburg, on Wednesday the nineteenth of February next, The houses and lots of the late Mrs Betty Randolph, deceased, together with a quantity of mahogany furniture, consisting of chairs, tables, mahogany and gilt framed looking glasses, and desks, a hansome carpet, a quantity of glass ware and table china, and a variety of other articles; also kitchen furniture complete. The above mentioned house is two story high, with four rooms on a floor, pleasantly situated on the great square, with every necessary outhouse convenient for a large family, garden and yard well paled in, stables to hold twelve horses, and room for two carriages, with several acres of pasture ground. Twelve months credit will be allowed for all sums above five pounds, on giving bond with approved security, to carry interest from the date if not punctually paid. The EXECUTORS. (Stephenson 1952).

The house was sold to Joseph Hornsby on February 21, 1783. Hornsby sold the property to Thomas Peachy sometime around 1800, but the record of the transaction has been lost. The house remained in the Peachy family until the late 1860s when it was sold to Richard Hansford. The succession of ownership for the remainder of the nineteenth century to the present is as follows:

| 1884-1893 | Moses R. Harrell |

| 1893-1897 | John Dahn |

| 1897-1920 | E.W. Warburton |

| 1920-1921 | Williamsburg Inc. (real estate company) |

| 1921-1927 | Mary Proctor Wilson |

| 1927-1938 | Merrill Proctor Ball |

| 1938-present | Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

Merrill Proctor Ball's daughter, Gertrude Deversa, continues to occupy the east wing of the house as her residence. Her recollections of living in "Mr. Speaker's" house are related in the oral history section of this report.

ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING

The Historic Area of the City of Williamsburg is situated along a drainage divide running east-west along the peninsula. The ravines cutting into the dividing ridge from the south eventually channel run-off water into the James River, whereas those on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street direct the flow into the York River. The area around the Peyton Randolph House has an elevation of about 80-85 feet above mean sea level. A fairly steep ravine which existed just to the east of the back lot became in the early 1940s the location for the Colonial Parkway tunnel.

Since the setting is now semi-urban, much of the flora around the Peyton Randolph House is cultivated rather than wild. Walnut, pecan, weeping willow, and crepe myrtle are but a few of the trees surrounding the yard. In earlier periods, however, Williamsburg had the characteristic flora of the Southeastern Coastal Plain—typified by temperate deciduous forests with areas of black and loblolly pines. 7 All of the Williamsburg area has been logged many times over the past 350 years, undoubtedly altering the landscape and ecology considerably.

Various faunal species common in the area in the eighteenth century are still found in Williamsburg and its environs. White-tailed deer, which are rather prolific on the outskirts of town, especially in protected areas along the Colonial Parkway, are not found in the Historic Area. However, grey squirrel, raccoon, opossum, skunk, rabbit, mice, and rats live peacefully within the town. Even occasional grey and red foxes are seen within the city limits. Birds common in the area include many types of water fowl, song birds, eagles, hawks, and vultures. Snakes, land and riverine turtles, fish, shellfish, and crabs are found in abundance in stream-side and marshland environments.

The climate of the Williamsburg area is fairly mild, mitigated by its proximity to the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The average annual temperature is 59° Fahrenheit, with the average winter temperature 38.9° F and the average summer temperature 76.8° F (Lewis 1975:141). Extremes in temperature do occur, however, both in the winter and the summer. Fifteen degree temperatures in January and February are not uncommon, and readings in excess of 100° F in July are predictable. The average annual rainfall is 42.5 inches, with occasional snow (Bick and Coch 1969).

8CHAPTER TWO:

PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGY

THE FIRST EXCAVATIONS

The first archaeological excavations in the Peyton Randolph back yard were begun by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Architecture Department in November 1938. The work was done under the direction of Francis Duke and was completed in the early fall of 1940 (The Archaeological Report is included in Appendix 3.) The primary objectives of the early excavations were to supply details for the reconstruction of the then no-longer standing east wing of the house, as well as for the most accurate possible restoration of the main house. One must assume the diggings in the back yard were aimed towards the eventual reconstruction of the various outbuildings, but only one small building was actually reconstructed. This structure, a shed, was constructed on original eighteenth-century foundations in 1940 (Photo 2).

The so-called "east wing" of the house was thought to have been a separate building, later connected to the original main structure by the central section. This building (Structure S) had been razed before modern memory, and does not appear in any of the early photographs of the Randolph House. The only evidence of the structure prior to the 1939 archaeology was its apparent presence on the Frenchman's Map and a "scar" left on the exterior east wall of the connecting central section (see Photo 3)—the only above-floor-level brick wall in the entire Peyton Randolph House.

Photo 2. - Reconstructed Outbuilding - Structure N

Photo 2. - Reconstructed Outbuilding - Structure N

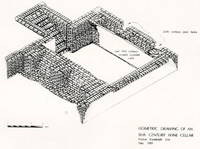

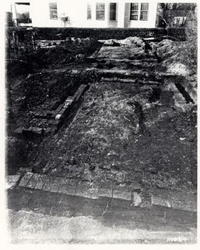

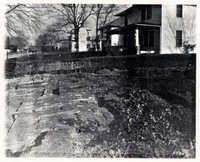

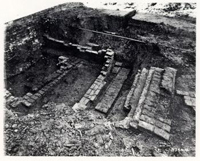

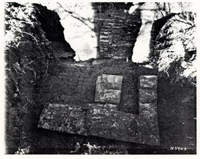

Excavations in 1939, prior to the construction of the house to its present appearance, revealed a 20 by 35 foot foundation some 15 inches thick forming a cellar under the east wing. The cellar had two levels of paving with a fireplace and chimney base built along its north wall.

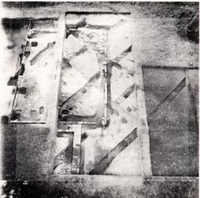

Many photographs were taken during the 1930s reconstruction/restoration and archaeology. One of the more revealing was taken of the excavated cellar in the east wing (Photo 4), showing a dump truck in the background. This confirms the suspicion that much of the fill removed from the site during the excavations was transported elsewhere. Given this indication, it appears, with little leap of logic,

10

Photo 3. - East Elevation of House, Before Restoration

Photo 3. - East Elevation of House, Before Restoration

Photo 4. - Excavation of the Foundations of Structure S in 1938

Photo 4. - Excavation of the Foundations of Structure S in 1938

that the backfill dumped after completion of the 1930s archaeology may have been brought in from another site. This supposition significantly affected the treatment of the backfill during the 1982-1985 excavations.

In addition to the excavation of the east wing foundations, the work in the late 1930s attempted to clarify changes in the various entrances to the house. Most significant among these were the entrances to the basement under the older west wing of the house. The excavators located a bulkhead entrance in approximately the same location as the reconstructed one is today, and another just to the east. The first entrance had been altered several times. The oldest entrance was from the north, but was changed to the west with the addition of the covered passageway from the kitchen. Later, the access to the basement was moved to the east and a porch placed over the former bulkhead. It is unlikely that the present reconstructed porch-tower existed at the same time as the covered passageway from the kitchen.

The outbuilding area, or back yard of the Peyton Randolph House, was also investigated in the 1930s. East of the marl walkway, which currently exists extending northward from the entrance to the central section of the house, the foundations of four outbuildings were located. Three were superimposed upon each other and probably represent storage buildings. The fourth was located just to the south of these and was reconstructed as a shed. More information regarding these structures is included in the main body of this report.

Documentation of the early excavations was reasonably complete considering the standards of the time period. Somewhat detailed maps were made of the excavation areas, and several photographs were taken which proved invaluable to the later excavators. Unfortunately, a significant amount of information was lost due to the destruction of several builder's trenches and the interruption of 11 stratigraphic sequences. Also unfortunate was the apparent apathy towards artifacts which is reflected in this passage from the 1939 Archaeological Report:

Few fragments, and none of importance, were found among the outbuildings. The east wing excavation yielded some china fragments in unusually good preservation, some of them being almost whole pieces. But nothing was found of particular architectural interest. Fragments were consigned to the Educational Department (Archaeology) (Duke 1939:15).

THE SECOND EXCAVATIONS

Another section of the current area of investigation was excavated in 1955, by a crew directed by James Knight of the Architecture Department. The method of excavation had by this time changed from the relatively haphazard digging carried out in the 1930s to systematic cross-trenching. The area cross-trenched extended from the edge of the earlier excavations all the way to Scotland Street, a plot of several acres. Three twentieth-century houses were still standing when the cross-trenching took place. Although the presence of these houses impeded the trenching operation, oral history informants maintain that all three structures contained basements, and thus the archaeological record in the area of the houses was already obliterated.

The newly-instituted method of cross-trenching consisted of digging parallel trenches to subsoil, measuring a shovel blade in width and a shovel handle apart, at forty-five degree angles to the north-south layout of the city. Such a technique would easily locate brick foundations. When a brick foundation was encountered, the walls were followed, thereby exposing the building. Scale drawings were made of the foundations, but no record was kept regarding the location of the trenches. Seven structures and a well were discovered during the 1955 excavations. Some regard for recovered artifacts was expressed at this time, although the provenience is less than exact and many fragments were given to the people who lived in the houses on the lot. Interviews with the surviving members of the excavation crew, and the results of the later archaeology, indicate that some soil around the newly-discovered foundations was screened (Derry and Brown 1987). The cross-trenches were refilled with virtually the same earth that was removed (except where screening occurred). This fact, given the great amount of area that was cross-trenched in the Historic Area during that period, greatly influenced the treatment of the trench backfill in the 1982-85 excavations.

THE THIRD EXCAVATIONS

The third excavations were a preliminary investigation of a portion of one of the outbuildings located during the 1955 cross-trenching expedition. These were conducted in the winter of 1977-78 by the Department of Archaeology under the direction of Ivor Noël Hume. An interim report on the findings, written by Eric Klingelhofer, is included in Appendix 4. This brief excavation was the first carried out by a trained archaeologist and the first to give credence to a refined 12 stratigraphic sequence. In addition, Mr. Klingelhofer's notes on the excavations were organized using the Harris Matrix System, a concept that was also employed in the later work. These preliminary excavations were limited to the western half of Structure A, which was then covered with a temporary structure rather than backfilled.

CHAPTER THREE:

METHOD AND TECHNIQUE

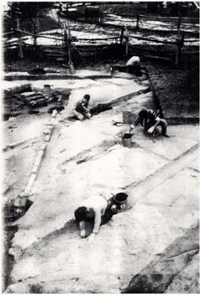

EXCAVATION

The back lot of the Peyton Randolph House was the first major excavation carried out by the newly-established Office of Excavation and Conservation. The specific goals of the project were primarily to provide information leading to the reconstruction of the appropriate dependencies, walkways, fence lines, garden features, and work areas. In addition to these rather straight-forward "where", "what", and "when" questions, there was the opportunity to address questions regarding, for example, the value of data gathered from disturbed contexts, the significance of close spatial control (even piece-plotting) on a prolific urban site, and the uses of in-depth soil analysis. Because of these and other more open-ended research goals at Peyton Randolph, the system used was an adaptation of a system that British archaeologists Biddle and Kjøbye-Biddle (1969), Barker (1982), and Harris (1979) have been using for many years known as "open area excavation." Open area, or "block," excavation does not use standing balks between squares for stratigraphic reference. Although the method was new to Colonial Williamsburg archaeology, and most historical archaeology done in the Tidewater Virginia area, it is hardly new to America. This approach was taken in the 1950s by Binford at Hatchery West (1970), and was presented as a method for carrying out settlement/subsistence studies in American archaeology by Struever in the 1960s (Struever 1968).

The decision to eliminate the traditional balks was prompted by a change in some research goals. Hester, Heizer, and Graham, in their text on field methods (1975), suggest that the square and balk method has primarily been used to explore "vertical" problems such as chronological sequences of artifacts. The best available chronological description of colonial artifacts, Noël Hume's Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (1969a), as well as a number of pamphlets and journal articles on the same subject, was a product of the square and balk method. However, Hester, Heizer, and Graham caution that "if one is seeking 'horizontal' information, then one should work for broad exposure of buried cultural remains, using large-area excavation" (1975:76). Because, as stated earlier, the purpose of the Peyton Randolph excavations is to offer a reconstruction of the back yard by detailing the nature of the spatial divisions and the use of particular areas in the past, broad horizontal exposure was a logical choice.

Vertical information need not be forfeited using this excavation approach. Sections formerly drawn from standing balks can be created from detailed elevation records and plan maps. Elevations are taken at least every 2.5 feet, more often in areas of complex stratigraphy. Many more cumulative section drawings can be generated from these records because one is not limited to those sections left 14 standing. Additionally, many archaeologists have found single standing sections "grossly misleading" (Barker 1982:44).

Open area excavation best suits large sites with complex stratigraphy, a description that aptly describes the Peyton Randolph site. Project goals required establishing the function of individual outbuildings or activity areas during various periods of use. This involved the isolation of living surfaces, features, and other deposits contemporary with the use of each building and the recognition of meaningful groups of features (macro-features). Of particular importance is the ability to accurately separate intact layers, then recognize and correlate contemporary stratigraphic units over a broad area. This has proven to be a complicated task for the Peyton Randolph back lot, where intensive occupation over two centuries has been combined with previous "archaeological" trenching to produce a very complex and disturbed stratigraphic sequence. Leaving many large unexcavated balks of soil would only obscure much of the stratification on the site, further complicating matters. To a field archaeologist trying to follow a consistent layer across a site, there is little difference between the destroyed stratigraphy in a 1955 cross-trench and the inaccessible strata in a standing balk.

In order to ensure that meaningful spatial patterning of the recovered artifacts at Peyton Randolph was recognized, a basic coordinate system was used to establish a grid. The north-south baseline was laid along North England Street, with "point zero," an arbitrarily selected point, near the corner of North England and Nicholson Streets. East-west grid coordinates were projected at ten-foot intervals from the north-south baseline. The site lies entirely within the northeast quadrant of the system. The ten-by-ten-foot units were laid out, and each was designated by its northwest corner stake. Each of these standard ten-foot squares was further subdivided into sixteen two-and-one-half foot sub-units. The exact horizontal and vertical coordinates of all diagnostic artifact groups, features and structural remains were also established using this grid system and a fixed datum point. Tightly controlled locational data was gathered so that, when appropriate, they could be subjected to computerized spatial mapping programs ranging from absolute three-dimensional graphic plotting to simulated two-dimensional distributional plotting (e.g., SASGRAPH). Such computerized mapping could supplement field identification of artifact concentrations and recognition of their broader spatial patterns through careful exposure in situ. Previous work on many historic sites has demonstrated the usefulness of these mapping programs in identifying specific patterns of refuse deposits and areas in which specific activities occurred. Many of these patterns and activity areas could not have been determined by visual inspection of excavation units alone.

Abandoning the extensive use of balks and increasing the control over provenience required some alteration in the recording system. Context numbers were given to both units of stratification and certain types of interfaces following the guidelines suggested in the Harris Matrix System, (Harris 1979:59). In order to reduce the size of the number labeled on individual artifacts, record spatial control, and facilitate computer mapping, each context number represents not only a particular unit of stratification, but a specific ten-foot section of that unit. For example, plowzone in the 250N 100E unit was given the context number 271, but the same layer in 260N 100E was given the number 272. Finer divisions of layers were obtained by dividing the unit into sixteen equal 2.5-foot-square sub-units, each designated by an alphabetic tag following the context number.

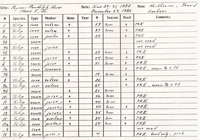

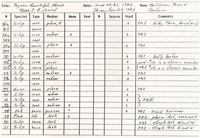

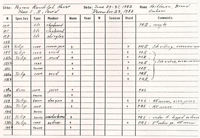

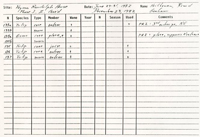

15Once a layer or a feature was uncovered and defined it was given a context number. These numbers were assigned sequentially as the context was defined. Each context was described on the CONTEXT RECORD SHEET (Fig. 3). A description of the form and its contents are as follows:

| 01. | CONTEXT # - | self-explanatory |

| 02. | PROJECT - | project name, e.g., PEYTON RANDOLPH |

| 03. | DATE - | date context number assigned |

| 04. | SITE - | block and area, e.g., 28G, 28H |

| 05. | UNIT - | coordinates of the northwestern corner of the unit containing the layer or feature being described. |

| 06. | TYPE - | what the context represented, e.g., plowzone, disturbance, layer, feature, post hole, etc. |

| 07. | GENERAL DESCRIPTION - | brief description of the location and salient characteristics of the context |

| 08. | STRATIGRAPHIC CONTEXT | relationship of the context with others |

| 09. | SOIL CONDITION | relative amount of moisture in the soil |

| 10. | SOIL COLOR | Munsell number |

| 11. | LT. MTR. | f-stop and shutter speed of light when the soil color determined (using standard setting of 100 ASA) |

| 12. | SOIL TEXTURE | relative amounts of clay, silt and sand |

| 13. | SAND TEXTURE | sand grain size |

| 14. | SOIL COHERENCE | degree of cohesiveness of soil particles |

| 15. | MOTTLINGS | description of the five most prevalent mottlings in order of frequency |

| 16. | ORGANIC REMAINS | choice of inclusions, if any |

| 17. | INORGANIC REMAINS | choice of inclusions, if any |

| 18. | BOUNDARY/INTERFACE DELINEATION | description of the area of contact between two contexts |

| 19. | SKETCH # | number of all field drawings in which the context appears |

| 20. | PHOTO # | number of all photographs in which the context appears |

| 21. | SOIL SAMPLE # | site plus context number |

| 22. | PEEL # | site plus context number |

| 23. | WET SCREEN # | site plus context number |

| 24. | RECORDED BY | three initials of the person filling out the form |

| 25. | EXCAVATED BY | three initials of the person(s) excavating the context |

| 26. | TPQ | terminus post quem date added to the record after artifacts have been examined by the lab |

| 27. | METHOD | whether the context was excavated by unit, sub-unit, or individually, and screen size |

| 28. | APPROVED BY | initials of the field technician who approved the information on the record |

| 29. | ENTERED BY | initials of the person entering the data into the computer |

In order to enter this data into a computer for easy management, two masks were created using INFOSTAR+ (version 1.6, 1984). The CONTEXT RECORD SHEET was divided into two forms for data entry purposes because of the large amount of disk space required for the more than 3000 contexts. The first mask contained all data on the sheet except the STRATIGRAPHIC CONTEXT information. The second mask containing this data was used to construct a Harris Matrix (Harris 1979). Ideally, the data gathered daily from the field would be entered as the excavations proceeded; however, due to a variety of circumstances, neither the hardware or the program necessary to enter the information was available until the excavations were virtually complete.

Since the most important aspect of site interpretation is based primarily on stratigraphic relationships, a brief explanation of the Harris Matrix System is in order:

The primary goal of the study of the stratification of a site is to make a stratigraphic sequence. The stratigraphic sequence may be defined as the sequence of the deposition of strata or the creation of feature interfaces on a site through the course of time (Harris 1979:86).

Simplistically a matrix diagram of the major layers in 28G would appear as follows:

TOPSOIL

CW TRENCHES

PLOWZONE

BSL 1

BSL 2

PLANTING BED 1

SUBSOIL

As the sequences were determined by the excavators, field technicians, and the site supervisor, the layers and features associated with those layers were excavated. The STRATIGRAPHIC CONTEXT section of the CONTEXT RECORD SHEET was filled out with the appropriate information. Those context numbers which denote the same layer or large feature were given a MACRO-FEATURE designation. This designation applies to a group of context numbers which compose a unit of study, such as plowzone, CW cross-trenches, or a structure. Combining these units of study according to how each relates to the other is done schematically using the matrix diagram. The diagram can then be separated into "periods," showing the changes chronologically through the occupation of the area. Periodization is "the process by which the stratigraphic material from a site is arranged into periods and phases based upon stratigraphic, structural and artifactual data" (Harris 1979:125). It is from this periodization process that the sequence of major events in the history of the Peyton Randolph back lot can be reconstructed.

SOIL ANALYSIS

Flotation (L. Vinciguerra and C. Thomas)

The flotation device used in processing soil samples from the Peyton Randolph Site consisted of two main sections. The base was a fifteen-gallon cylindrical tank made of NALGENE. Two holes were drilled through the wall of the tank, near the base. One was fitted with a plug, to serve as a drain for emptying the tank between samples. Through the other, an L-shaped length of copper pipe was fitted which ran upward through the center of the tank. An adjustable spray nozzle was attached to this pipe.

The upper portion of the device was constructed of a twenty-quart utility tub. A shallow, rectangular hole was cut near the upper edge, and a broad, flat spout attached. The bottom of the tub was removed and replaced with 24 by 24 brass mesh cloth (wire diameter: 0.014"), which retained all particles greater than 0.0277" (0.70 mm). The tub was selected to create a snug, water-tight fit when pressed down into the top of the NALGENE tank.

Aluminum baking pans were used for collection of the floated material. The bottoms of these pans were cut out and replaced with 40-mesh brass wire strainer cloth, which would collect all particles at least .0175" in diameter.

Flotation was conducted during the winter months and therefore had to be done indoors. A large double sink was installed in the O.E.C. field trailer in order to facilitate the process. The water was run at low pressure into the base tank from the bottom until it filled the tank and spilled over the spout. Then, at high pressure, the stream of water was directed through the screen to create turbulence. The sample was then sprinkled into the sample bucket. The "light fraction" was then carried through the spout and into the collecting tray. The sample could be agitated gently by hand to break up any highly coherent soil, if necessary. The process continued until there was no further suspended material visible in the flow to the collecting tray. The tray was then set aside on a wire rack for air drying. The "heavy fraction" was retained in the screen fitted in the NALGENE tank. The water was drained and the sample extracted between each process.

This method of collecting flotation samples minimizes handling of the delicate material, which is especially fragile when wet. The standard poppy seed test, i.e., placing 100 poppy seeds in the sample before it is processed and counting them after flotation, produced an average recovery rate of 95.596. This test was run periodically to monitor the condition of the screens, adhesives, and fittings.

Chemical analysis

Soil samples recovered from Peyton Randolph were subjected to various chemical tests as soon after they were collected as possible. All samples were tested for pH. The distribution of pH values appeared randomly dispersed with no concentrations of high or low values in any particular area. Chemical analysis of soil from specific features included testing for phosphates, humus, potassium, and 19 nitrogen. The testing was carried out by Field Technicians Charles Thomas and Lucie Vinciguerra. The soil chemistry data is on file at the Department of Archaeological Research. Any significant findings are included in the discussion of the various features.

ARTIFACT ANALYSIS

Artifacts recovered in the field were brought into the O.E.C. Laboratory on a daily basis. As quickly as possible, the bags were emptied and washed according to established laboratory procedure. After washing, artifacts were dried, sorted into categories, and labelled with the site and provenience number. Oyster shell, brick fragments, and some iron pieces were counted and placed in temporary storage. The remainder of the artifacts were coded according to type. Computer cards were key-punched with the appropriate codes and fed into a mainframe computer at the College of William and Mary. The coded and entered artifact lots were left in open storage in Study Collection Rooms 1 and 2 until the end of the report-writing process. All faunal material was remanded to the Staff Zooarchaeologist, and any artifact in need of conservation was removed to the Conservator. Ceramic and some glass artifacts were mended and cross-mended under the direction of the Collections Supervisor, in consultation with the Site Supervisor. Until completion of all reporting activities, the artifacts remained in open access for analysis and study.

SPECIAL STUDIES

Pollen and parasite analysis

A total of twenty-one soil samples were extracted from various sections of the site for palynological and parasitological analysis. Eight of the sixteen samples taken for pollen analysis were from several levels within the fill of each of the four planting beds. One was from the buried "A" horizon within the interior of Structure A, one from the marl yard spread associated with Structure L in the 28H area, and another from the ash layer within the hearth of Structure K. Five more samples served as control samples for the analysis. Only five samples were selected for parasite analysis: one from each of the four planting beds and one from the BSL 2 sheet refuse layer in 28G.

The samples were sent to Dr. Karl J. Reinhard at the Biology Department of Texas A&M University for analysis. His full report is included in Appendix 5. Since the presence or absence of pollen and parasites in the Peyton Randolph soils was unknown, only a few samples were sent for analysis. The results were disappointing. No parasite remains were found in any of the samples investigated, and only one of the sixteen samples slated for pollen analysis contained a sufficient number of pollen grains (>200 per gram of soil) to be of any analytical significance. This sample was 28G/1484A, a section of the paved bottom of Planting Bed 3. The most prevalent pollen type was that of the pine, both a very common tree in the area and a very prolific producer of pollen. A full list of the plants in each of the contexts studied may be found in Table 4 of Dr. Reinhard's report.

20The soils of the Peyton Randolph site, and probably those of most of the Williamsburg area, are not conducive to pollen or parasite preservation. Discrete features such as privies may have been more informative as parasite and pollen remains might have been preserved in these more organic soils. Since no privies were encountered at Peyton Randolph, the planting beds would have seemed to provide the best possible alternative as discrete, undisturbed deposits. This was unfortunately not the case.

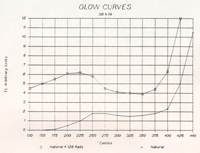

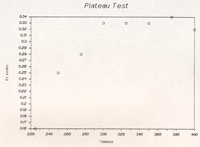

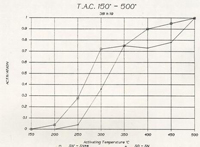

Thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence (TL) is an absolute dating technique dependent upon the measurement of stored energy released as light when a previously heated substance is re-heated. In soils or clay, grains of quartzite and feldspar accumulate natural radioactive impurities which are released when the particles are heated to temperatures in the range of 300-500° C. The gradual re-accumulation of these impurities can be measured to yield the date of the last firing. Dating of ceramics and glass by this method has been successfully used in archaeology (Ralph and Han 1966; Zimmerman and Huxtable 1970).

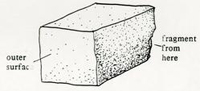

Assuming local brick was fired to such temperatures when manufactured, TL could then be used to determine the age of brick used in Williamsburg buildings. Environmental factors, especially moisture, contribute substantially to the accuracy of the derived date, and a controlled study of these factors should be linked to the TL process. As a preliminary experiment, a brick from Structure D was sent to a TL laboratory in Oxford, England, in order to find out whether a proper signal could be obtained from Williamsburg-area brick. The signal was indeed sufficient for dating, even though the environmental factors were not considered and to date derived was, as expected, not accurate. Studies in the TL dating of brick and glass from Williamsburg will hopefully be continued by the Foundation based upon the success of this experiment.

The report on the brick from Structure D, as performed by the laboratory in Oxford, is included in Appendix 9.

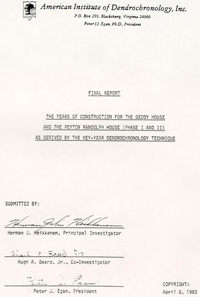

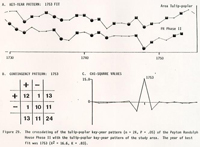

Dendrochronology

Though the tree-ring dating of various parts of the Peyton Randolph House is not directly related to the archaeology of the back yard, the process was carried out during the excavations and the results have bearing on the archaeological finds. A final report on the dendrochronology of the James Geddy and Peyton Randolph Houses was submitted to the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Architectural Research by the American Institute of Dendrochronology, Inc. of Blacksburg, Virginia on April 8, 1983. (The full report is included in Appendix 8.) The dendrochronological dates for the older west wing of the Peyton Randolph House correspond with the known historical record in that the joists, sleepers, and plate of the second floor ceiling date to 1715, the roof to 1716, and the gutters to 1718. William Robertson bought the property in late 1714 and was required to build upon the lot within two years. Though no datable wood remains were recovered from the back lot archaeologically, the 1715 date for the construction of the house would logically place some of the outbuildings uncovered within the same time 21 frame. A date of 1753 for the mid-section was derived from cross-dating the tulip poplar samples from the roof structure of the mid-section with the area's oak/pine key dates (see Appendix 10).

Archaeo-botanical analysis (Stephen Mrozowski)

Soil samples from various features excavated at the Peyton Randolph site were subjected to flotation, described above, for retrieval of macrofossil remains. The plant macrofossils were sent to Stephen Mrozowski, National Park Service Archaeologist in Boston, Massachusetts, for identification and interpretation. For a variety of reasons explained in his report, the results of the study were disappointing. However, much was learned regarding the kinds of contexts most suited for this type of analysis in the future. The results of his study, and the methodology involved, is included in full in Appendix 6 of this report.

Faunal remains (Joanne Bowen Gaynor)

Begun in August 1983, the identification of the faunal remains from Peyton-Randolph has run concurrently with the excavation of the site. The identification procedures and the methods used to analyze this resource have been carefully adapted to the specific problems and characteristics of the Peyton-Randolph site. With the ongoing excavations that produced huge numbers of bone fragments (a total of 48,206), the challenge was to work efficiently, processing and analyzing the bone in such a way that all potentially important data on the animals and any alterations caused by cultural and natural variables were recorded.

Goals set for this preliminary phase of faunal analysis were: first, to develop procedures which would efficiently process bone, sorting the identifiable from the unidentifiable fragments and numbering only the identifiable fragments; second, to focus the identification and recording process on only the potentially important contexts; and third, to identify discrete contexts with known quantities of bone, assess their research potential, and begin the analysis and interpretation of these assemblages.

The recording of the data during the identification process was aimed at recording as much information as possible to cover the main questions in zooarchaeological research today. Basic biological characteristics of the bone were recorded. These included the element, portion (i.e., complete, proximal, distal), side, and relative size and age of the individual. For all fragments exhibiting any distinguishable age characteristics, they were recorded. Two of these characteristics are the soft grainy texture of very young, immature individuals, and the state of epiphyseal fusion. The effects of taphonomic processes were recorded, and if applicable their specific location on the bone. These included weathering and rodent or carnivore chewing. Cultural alterations, including burning and butchering cuts and marks on the bone, were recorded.

Whenever archaeological and artifact analysis identified discrete contexts, analysis of bones from these assemblages was pursued. One of these projects was to analyze the fragments from the planting beds as non-dietary remains (see Appendix 13). Another, done in conjunction with Linda Derry, was to compare 22 samples of bones from 1955 cross-trenches with their corresponding stratigraphic layer to see if there were any significant differences between the two samples (see Derry and Brown 1987).

Currently at least three research projects have been identified for the faunal remains. One is to examine the development of cattle husbandry in the eighteenth century, using the large number of well preserved cattle remains from the planting beds to determine the size range and specific characteristics of cattle in the early eighteenth century (Maltby 1982). Then, by drawing upon all other measurable cattle bones from tightly-dated contexts, show how cattle developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

A second project outlined for the planting bed cattle remains is to study the process of cattle butchering process in the early eighteenth century. A third project outlined for the Peyton Randolph faunal remains is to examine the diet of the Randolph households. Given the secondary nature of most of the deposits excavated from the site and their questionable association with the Randolph households, analysis has focused on the two occupation layers, BSL I and BSL II.

CHAPTER FOUR:

DESCRIPTION OF MAJOR FINDS

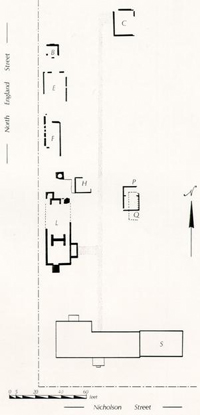

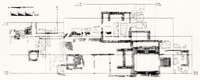

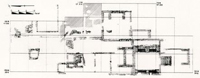

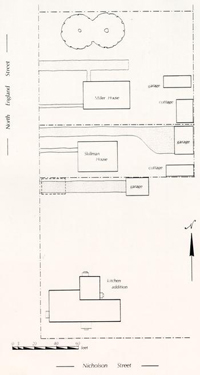

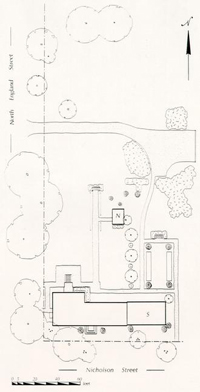

Block 28, which contains the Peyton Randolph lot, was divided into several so-called "archaeological areas" before the first excavations in the 1930s. The three areas that were re-excavated in 1982-1985—B, G, and H—are shown in Figure 4.

Although these area designations are purely arbitrary, the areas are described separately for several reasons. First, and most importantly, areas G and H appear to have been used differently during the past. Second, it is more convenient for the descriptive reporting. The 28B area is described with the 28H area, however, because of its paucity of information and its proximity to the latter area.

The following sections describe the major layers and the structural remains found in the 28G area. Measurements are given in tenths and hundredths of feet rather than in inches. This is a standard compromise with the metric system prevalent in the Tidewater area. In order to restrict the often repetitive word clutter that accompanies descriptive text, the first measurement given, for example, of a post hole, is always the north-south axis. The second measurement is the east-west axis, and the third is the depth. This is standard for the description of any feature or structural remains.

24 Fig. 4 - Overall Map of Excavation Area

Fig. 4 - Overall Map of Excavation Area

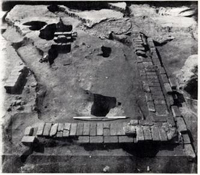

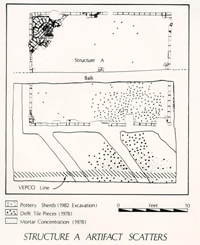

IV.A. STRUCTURE A - EARLY EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY DWELLING

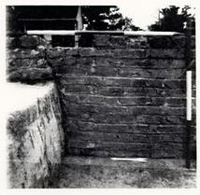

Structure A was first excavated during the 1955 exploration of the Peyton Randolph back lot (Photo 5, above). It was probably a wood frame building measuring approximately 20 by 16 feet, containing a hearth in the northeastern corner. The building's sill was supported by nine brick piers. The presence of the piers was hidden from exterior view because the area between them was filled by a one-brick-wide string course. The bricks in the string course were of the same firing and size as those of the piers, so it may be assumed they were contemporary. The purpose of the "façade" of string brick was either one of aesthetics, making the building appear it was more substantial than it actually was, or one of practicality, perhaps helping keep unwanted animals from under the house. The filler bricks supported little weight since many of them were simply laid one on top of the other without benefit of mortar or the interlock needed to support a sill. The depth of the facade and piers varied from three courses in the east to five in the west. This compensated for the natural slope of the land towards North England Street, and for the continuing compaction of a seventeenth-century drainage/boundary ditch upon which Structure A had been constructed. The builders of Structure A were apparently well aware of the earlier ditch because the southwestern pier of the structure rested on a line of rowlock brick placed across the feature (Photo 6). The support brick were also the same as the building brick, evidence that they were laid before the house was built in anticipation of compaction problems.

Even though the foundations of the small structure had been previously excavated, much archaeological evidence pertaining to the construction of the building remained. A large support beam probably ran north to south under the

26

Figure 5 - Placement of Joist Nails, Interior Structure A

27

floor through the center of the structure since three central bricks lined up in this direction. No comparable arrangement ran east to west. Impressions of the sill had been left in the wet mortar on the exterior of the chimney base. The size of the sill was surprisingly small, little more than 4.5", based on the slight elevation difference between the wall foundation and the firebox or floor level. Several rows of upright nails found in situ in the southeastern corner of Structure A suggest wooden joists approximately two feet apart with floor boards running north-south (Fig. opposite).

Figure 5 - Placement of Joist Nails, Interior Structure A

27

floor through the center of the structure since three central bricks lined up in this direction. No comparable arrangement ran east to west. Impressions of the sill had been left in the wet mortar on the exterior of the chimney base. The size of the sill was surprisingly small, little more than 4.5", based on the slight elevation difference between the wall foundation and the firebox or floor level. Several rows of upright nails found in situ in the southeastern corner of Structure A suggest wooden joists approximately two feet apart with floor boards running north-south (Fig. opposite).

Photo 6. - Rowlock Wall Under Foundations of Structure A

Photo 6. - Rowlock Wall Under Foundations of Structure A

The small corner fireplace (Fig. 6, below right) was contained by the north and east exterior walls of the structure. Five courses of brick remained, and while the top three were well-mortared, the bottom two were held in place by a fine sand mixed with oyster shell bits. The bottom course rested on subsoil, and extra brick were placed around it to fill the gap between the base and the walls. The fourth course from the bottom contained one brick which was mortared to the top of the northeastern pier. Sufficient area remained on top of this pier, however, for the sill to have been in place when the chimney was constructed. The possibility that the fireplace was an addition to a standing building rather than original to its construction cannot be ruled out.

Figure 6. - Detail of Corner Fireplace, Structure A

Figure 6. - Detail of Corner Fireplace, Structure A

The firebox consisted of one course of brick mortared to redeposited fill at the level of the fourth course from the bottom. The fill contained ash, plaster, mortar, and rubble, but no diagnostic artifacts. A circular area of the firebox was heavily burned, and the bricks were black, worn, and 28 crumbled. The hearth bricks in front of the firebox were mortared onto fill, and the outer or southwestern edge had fallen and slumped downward. The fill was similar to that under the firebox, containing ash, mortar, plaster and brick (only in lesser amounts). As few artifacts were found in the fireplace fill, no date was obtained for this part of the chimney feature either. However, one artifact of note was found in this fill: a manganese decorated delft tile fragment. This may indicate a repair or rebuilding of the hearth and fireplace, but more likely it was a residual artifact already in the fill and has no connection with Structure A's fireplace.

Photo 7. - Detail of Fireplace "Wing"

Photo 7. - Detail of Fireplace "Wing"

Also of note were two brick pads or "wings" on either side of the chimney base (Photo 7, above). Neither of these "wings" was mortared to the chimney base, although the two remaining courses in the northwest "wing" were mortared to each other. This mortar layer and the upper course of bricks extended northward over the former sill. Impressions of what is believed to be that sill remained on the underside of the mortar. Elevations taken on these bricks indicate a sill of approximately 4.5". The other bricks of the "wing" were mortared onto redeposited fill similar in color to that found under the firebox. Again, unfortunately, no diagnostic artifacts were found. The southeast "wing" consisted of only one course, and was badly damaged by a later posthole which destroyed part of the chimney base in the same area. Neither of these "wings" was designed to bear substantial weight, for unlike the chimney base they rested on redeposited fill rather than stable subsoil. One must assume these corners to the fireplace were flooring or low shelves filling the gap in the interior between the chimney and the walls.

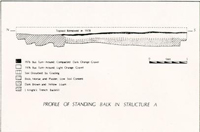

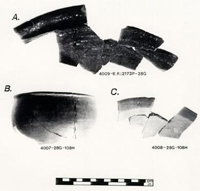

The demise of Structure A is illustrated in soil differences evident in a balk left standing within the interior of the structure (Fig. 7). Under the topsoil and the remnants of a 1975-76 bus turnaround, the interior of Structure A contained four major layers. The uppermost layer (28G/81) was a mixture of brick rubble, mortar, and plaster with very little soil or artifacts. The western half of this layer was excavated in 1978. The second layer (28G/88) contained a concentration of plaster as well as numerous mid-eighteenth-century artifacts. Under the plaster was a layer of dark brown and yellow loam (28G/108) [Munsell: 10YR5/6], containing numerous artifacts and some charcoal. The fourth and last stratigraphic layer, before subsoil, was a medium brown loam [Munsell: 10YR5/3], which was probably the original topsoil present when Structure A was built. Unfortunately, it contained few artifacts. Eight cross-mends between the brownish yellow loam and the plaster layer indicate they were part of a similar or the same series of events. No cross-mends were associated with the other two layers, but this was not

29

Figure 7. - Profile of Standing Balk in Structure A

unexpected since only 26 of the 434 sherds found within the structure came from the rubble and buried topsoil layers.

Figure 7. - Profile of Standing Balk in Structure A

unexpected since only 26 of the 434 sherds found within the structure came from the rubble and buried topsoil layers.

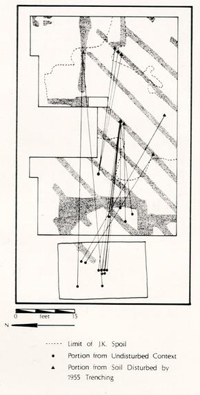

None of these layers can be physically associated with layers outside the structure since the 1955 cross-trenching followed the brick foundation walls all the way around the structure, leaving an island of undisturbed strata in the interior. The association was partially reconstructed through cross-mends. Several layers excavated outside the west wall of Structure A in 1978 contained ceramic fragments which cross-mended with the two artifact bearing layers on the interior. Figure 8 illustrates these layers, the thirty cross-mends, and reconstructed elevations. These exterior layers were described by Eric Klingelhofer in his "Interim Notes" (see Appendix 4) and include a thick mortar layer (ER2175F) sealing a half-inch deposit of brown loam (ER2175J) that contained numerous shell fragments, then another half-inch of ashy loam (ER2175K). These layers sealed a one-inch layer of loam (ER2175L) containing mortar, plaster, brickbats, and numerous fragments of delft tile. Under this tile layer was another ashy loam layer (ER2175M, N), sealing a large scatter of pipe stems (ER2179A). These pipe stems created a fairly flat surface over a two-inch layer of brown loam (ER2175T) and two deposits interpreted as the infilling of depressions in the brown loam (ER2171J and ER2175P). Below the brown loam and above natural was reportedly a three-inch layer of buff sandy loam (ER2175V).

Klingelhofer thought these layers represented the daily sweepings from Sir John Randolph's law office (pipe stem layer ER2179A), a renovation (mortar, plaster, and tile layers), a dower house for Lady Randolph (loam layers ER2175J

and K), and then demolition (mortar spread ER2175G). However, cross-mends illustrated in Figure 8 indicate that everything from the ashy loam (ER2175M) beneath the delft

30

Figure 8 - Cross-Mends to 1955 Trench Fill, Structure A

31

tiles up to the mortar spread (ER2175G) was destruction debris. Though this was described as five layers, only two inches existed between the mortar and the ashy loam. In fact, all of these layers also cross-mended to each other (Fig. 8). This certainly supports the argument that all these layers represent one event of relatively short duration rather than renovation, use, and destruction.

Figure 8 - Cross-Mends to 1955 Trench Fill, Structure A

31

tiles up to the mortar spread (ER2175G) was destruction debris. Though this was described as five layers, only two inches existed between the mortar and the ashy loam. In fact, all of these layers also cross-mended to each other (Fig. 8). This certainly supports the argument that all these layers represent one event of relatively short duration rather than renovation, use, and destruction.